‘Design Problems’ are notoriously difficult to pin down and define. In fact, the initial intractable-seeming nature of design problems – often referred to by Rittel’s term of ‘Wicked Problems’ – can almost be seen as defining features of both design and design research. Action Research is a research methodology, well-established in the social sciences, which has much to offer design research.

Action Research is a family of research methodologies characterized by their:

- Focus on experimental methods;

- Participatory nature;

- Focus on practice and processes of learning; and

- Ongoing dialog between the research participants.

Like all design research Action Research is a context-dependent activity – but unlike in many other forms of design research in an Action Research environment the context itself continues to change and be modified during the course of the research process itself. This in fact is where it’s power lies as a design research methodology.

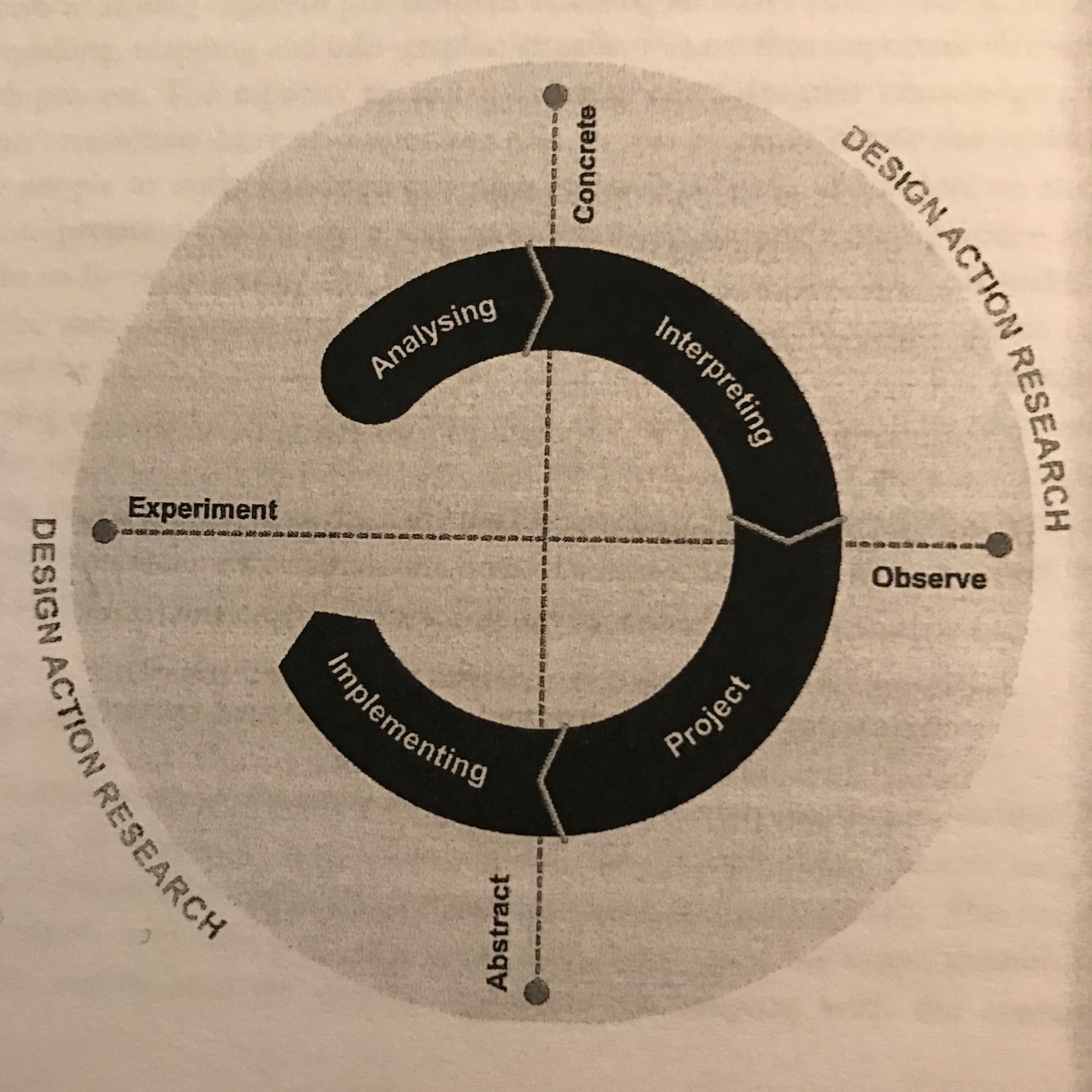

As data emerges from the research process it feeds back into the research process itself opening up new possibilities for the use of different tools, techniques, and methodologies to examine the ‘design problem’ in question. As the research process ‘unfolds’ other types of design research methodologies, such as prototyping and experimentation can be brought in as required, to deepen and build out the design process. This is made clear in the following diagram:

Figure 1: Action Research in Design (taken from Villari 2015)

As this diagram makes clear, Action Research in a design context is generally structured around four general stages:

- Analysing;

- Interpreting;

- Designing; and

- Experimenting.

The participatory nature of this approach is particularly strong with the participants best seen as being a community of inquiry. What this approach is particularly good at is opening up the democratic nature of this mode of inquiry and the necessarily self-reflective and relational aspect of effective design research. While the terms ‘empathy’ and ‘human-centered’ are increasingly utilized when discussing design their role in Design Research – their active role in how this is taught and practiced by many

A key aspect to successful Action Research in a design context then is the ability of the researcher to provide enough structure to empower and guide the participants without constraining their ability to imagine and play. While this is always a good practice for any form of design research facilitation this is even more so the case in Action Research where the evolving nature of the process and the ‘Design Problem’ itself is dependent on the role of the researcher providing ongoing guidance during the research process. Done well this process can open up new ways of seeing – with the possibility of shifting the very frame of reference in which the design problem is contextualized. Done badly, the process can severely delimit the scope of the possible design outcomes that can emerge.

The key to the successful use of Action Research in design is for design researchers to:

- Focus on building out the relationships between the participants of the research process (both people and artifacts); and

- Help manifest in a concrete way the different ideas that emerge from the ongoing design process – including more intangible concepts and ideas that may emerge.

Combined these processes help ensure that the true strength of Action Research is able to be brought to the very specific contexts that design research is concerned with.

While particularly useful for social design, Action Research has a definite place in all types of design from Industrial Design, Interaction Design, and even Architecture. It’s evolving and participatory nature has much in common with other new design methodologies such as Experiential Futures. These, and other emerging design research techniques and methodologies, offer much to the ongoing development of our profession as designers and the effectiveness and quality of what we design.

Additional images courtesy of: Pixabay